Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute and AlveoliX have developed a groundbreaking model known as the first human lung-on-a-chip, which is designed to enhance personalized medicine. Published in the journal Science Advances, the study showcases how this innovative technology uses stem cells derived from a single human donor to simulate lung functions and diseases, particularly focusing on the early stages of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection.

Alveoli, the air sacs in the lungs, play a crucial role in gas exchange and serve as a barrier against respiratory diseases such as influenza and tuberculosis. Despite their importance, creating effective and accessible models to study human respiratory diseases has remained a challenge. This new lung-on-a-chip model bridges that gap, offering a way to explore individual responses to infections and potential treatments.

Innovative Technology for Disease Research

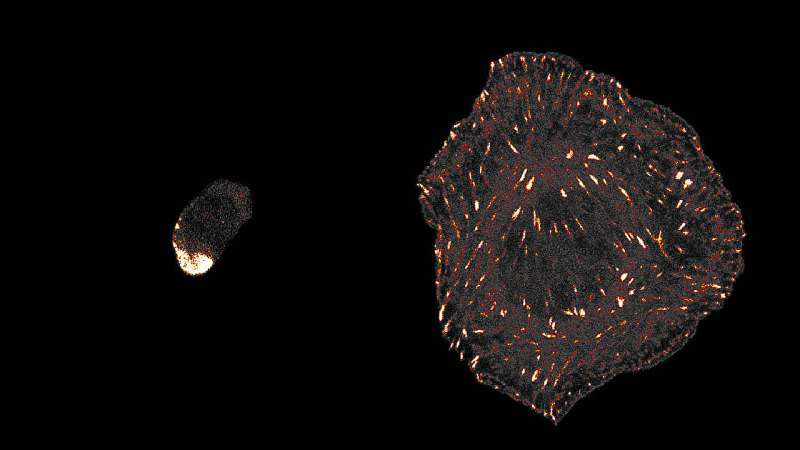

The research team successfully produced type I and II alveolar epithelial cells, along with vascular endothelial cells, from human-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). These cells were grown on a specialized thin membrane within a device engineered by AlveoliX, creating a functional air sac barrier. The team implemented rhythmic three-dimensional stretching forces to mimic the natural motion of breathing, allowing for a more accurate representation of lung behavior.

According to Max Gutierrez, PhD, principal group leader at the Crick and corresponding author of the study, this organ-on-chip approach helps eliminate discrepancies found in traditional animal testing. “Given the increasing need for non-animal technologies, organ-on-chip approaches are becoming ever more important to recreate human systems,” he stated. The genetically identical cells used in these chips can be tailored to reflect specific genetic mutations, leading to a deeper understanding of how diseases like tuberculosis affect individuals.

Insights into Tuberculosis Progression

The study revealed significant findings regarding tuberculosis infection. In chips infected with TB, researchers observed large clusters of macrophages, some of which contained necrotic cores—areas of dead macrophages surrounded by living cells. By the fifth day post-infection, both the endothelial and epithelial barriers had collapsed, indicating a breakdown of normal air sac function.

Jakson Luk, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at the Crick and first author of the study, emphasized the importance of understanding the early stages of TB, which can take months to show symptoms. “We were successfully able to mimic these initial events in TB progression, giving a holistic picture of how different lung cells respond to infections,” Luk explained.

The researchers express excitement about the potential applications of this new model, which could extend beyond tuberculosis to include other respiratory infections and conditions such as lung cancer. They are now looking to refine the chip further by incorporating additional relevant cell types.

This innovative research marks a significant advancement in the field of personalized medicine, paving the way for more effective treatments tailored to individual patients. As scientists continue to explore the implications of this lung-on-a-chip technology, its potential to transform medical research and patient care remains promising.