Research led by scientists at New York University has uncovered thousands of preserved metabolic molecules in fossilized bones dating back millions of years. This groundbreaking discovery offers an unprecedented glimpse into the diets, diseases, and climates of prehistoric animals, suggesting that many environments were significantly warmer and wetter than those present today.

The findings, published in the journal Nature, represent a major advancement in the study of ancient ecosystems. For the first time, researchers successfully analyzed metabolism-related molecules preserved within fossilized bones from animals that lived between 1.3 million and 3 million years ago. This innovative approach could reshape how scientists reconstruct the biological and environmental contexts of lost worlds.

Revealing Ancient Ecosystems

By studying these chemical traces, the team was able to glean vital information about the animals’ health, diet, and the ecosystems they inhabited. The metabolic signals allowed researchers to reconstruct critical details such as temperature, soil conditions, and rainfall. The results indicate that the regions studied, particularly in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa, were once home to lush environments, in stark contrast to the climates observed today.

Timothy Bromage, a professor of molecular pathobiology at NYU College of Dentistry and the leader of the research team, noted, “I’ve always had an interest in metabolism… it turns out that bone, including fossilized bone, is filled with metabolites.” This research opens up new avenues for understanding how prehistoric organisms interacted with their environments.

Pioneering Techniques in Paleontology

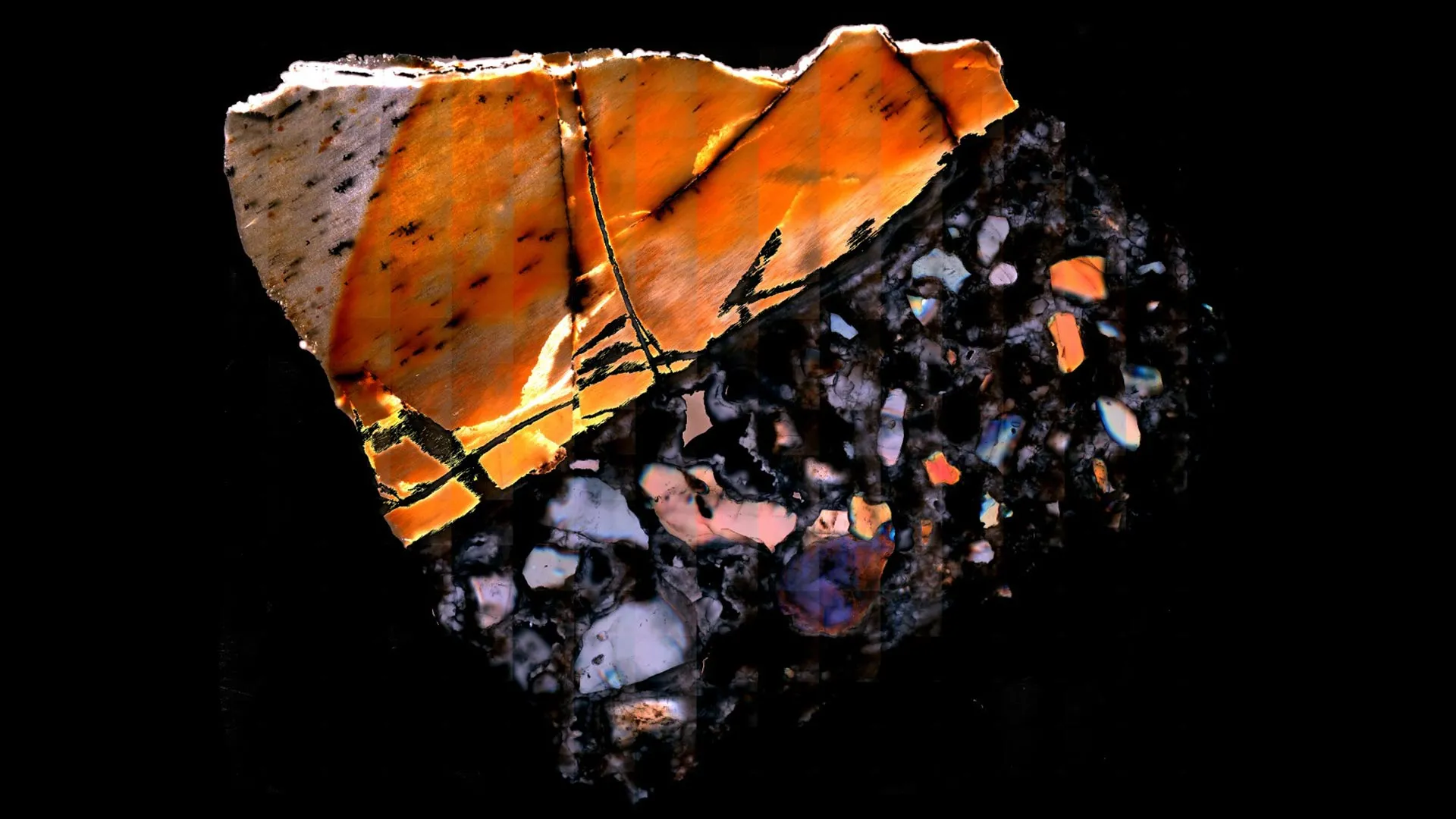

The study examined fossilized bones from various animals, including rodents and larger species like antelopes and elephants. Utilizing mass spectrometry, a technique that identifies molecules by converting them into charged particles, researchers identified thousands of metabolites. In tests conducted on modern mouse bones, nearly 2,200 metabolites were detected, providing a comparison for the fossil samples.

Some metabolites detected in the ancient bones reflected normal biological processes, including the breakdown of amino acids and carbohydrates. Notably, certain metabolites indicated health issues in the animals. For instance, a ground squirrel bone from Olduvai Gorge, dated to about 1.8 million years ago, showed evidence of infection from the parasite Trypanosoma brucei, which causes sleeping sickness in humans.

Bromage explained that the bone of the squirrel contained a unique metabolite released into the bloodstream by the parasite, alongside a detectable anti-inflammatory response from the host. This remarkable discovery serves as a testament to the potential of metabolomics in paleontological studies.

The research team was able to identify dietary habits as well. By analyzing plant metabolites, the scientists found compounds linked to local flora such as aloe and asparagus. Bromage elaborated, “What that means is… the squirrel nibbled on aloe and took those metabolites into its own bloodstream.” This information allows researchers to reconstruct the environmental conditions in which these animals lived, providing insights into the ancient ecosystems they inhabited.

The collaborative effort brought together experts from several institutions, including researchers from France, Germany, Canada, and the United States. The study was supported by The Leakey Foundation, with additional funding for equipment provided by the National Institutes of Health.

As this research demonstrates, the application of metabolomics to fossil studies could revolutionize our understanding of prehistoric life, offering a level of detail that was previously unattainable. Scientists now have a new tool for investigating the intricate relationships between ancient organisms and their environments, paving the way for further discoveries in the field of paleontology.