The increasing number of objects in Earth’s orbit has prompted urgent discussions about satellite safety. Currently, more than 45,000 human-made objects circle our planet, a figure that includes satellites for communication and navigation, as well as space debris from earlier missions. As the launch schedule for new technologies intensifies, particularly with plans for 2026, finding ways to prevent potential collisions has become essential.

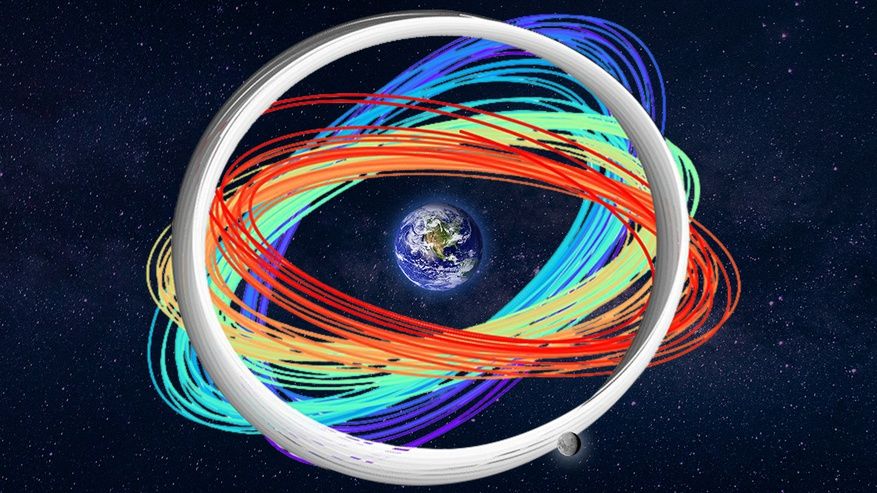

Researchers at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in California have developed an innovative approach to modeling orbits in what is known as cislunar space, the area between Earth and the moon. Their new mapping method outlines 1 million potential orbits over a simulated six-year period. This analysis uses a publicly available database and extensive processing capabilities from LLNL’s advanced supercomputers.

As various countries and private entities continue to launch satellites, the likelihood of crowding and subsequent collisions increases. This research is particularly timely, given the growing interest in lunar missions and the expansion of satellite constellations.

Denvir Higgins, a scientist at LLNL, highlighted the advantages of modeling such a vast number of orbits, stating, “When you have a million orbits, you can get a really rich analysis using machine learning applications.” This method enables researchers to predict the stability and longevity of orbits and to identify any anomalies that may indicate potential risks.

The findings from the simulations reveal that approximately half of the modeled orbits remained stable for at least one year, while just under 10% maintained stability for the entire six-year period. According to LLNL scientist Travis Yeager, anticipating a satellite’s position in the future is complex: “If you want to know where a satellite is in a week, there’s no equation that can actually tell you where it’s going to be. You have to step forward a little bit at a time.”

The computational demands of simulating one million orbits over six years are significant, requiring 1.6 million CPU hours. To put this into perspective, processing this data on a single computer would take over 182 years. However, using the lab’s state-of-the-art Quartz and Ruby supercomputers, the team completed the simulations in just three days.

This research not only enhances our understanding of orbital dynamics but could also aid in identifying busy intersections for satellites. As more countries embark on satellite launches without coordinated efforts, this mapping tool could prove invaluable in ensuring the safety and sustainability of space operations.

As the challenges of managing a crowded orbit continue to grow, innovative solutions like those developed at LLNL will play a critical role in safeguarding both current and future space missions.