Research conducted at the University of Manchester has provided new insights into how the immune system in the gut changes following a stroke and its potential role in gastrointestinal issues experienced by patients. The study, published in the journal Brain, Behavior and Immunity, supports the growing concept of the “gut-brain axis,” which suggests that communication exists between the gut and brain in both health and disease.

Stroke is a critical medical emergency that disrupts blood flow to the brain, often leading to long-lasting effects on mobility and cognitive function. Many stroke survivors face additional challenges, including increased susceptibility to secondary bacterial infections and gastrointestinal symptoms such as swallowing difficulties and constipation. Emerging research indicates these complications may be linked to alterations in the gut’s microbiota, the community of beneficial bacteria essential for digestive health.

Despite previous findings indicating that changes in the gut microbiome occur in stroke patients and animal models, the reasons behind these gastrointestinal symptoms and their impact on recovery have remained unclear. Prior research by the same team has shown that signals from the nervous system can influence gut immune responses after a stroke. The latest findings suggest a bidirectional relationship, where immune cells producing antibodies migrate to the brain during a stroke. The significance of this migration for stroke severity and patient prognosis is still being investigated.

Using mouse models, the research team examined the changes in the small intestine following a stroke. They discovered that populations of immune cells responsible for producing antibodies were altered within the initial days post-stroke. Notably, a specific subset of cells that produce Immunoglobulin A (IgA) became hyper-activated. IgA plays a crucial role in regulating the populations of commensal bacteria in the gut, thereby influencing gut health.

Interestingly, the researchers found that mice lacking IgA did not exhibit the same alterations in their gut microbiome after a stroke, implying that dysfunctional immune responses could partially explain the gastrointestinal changes observed in stroke patients.

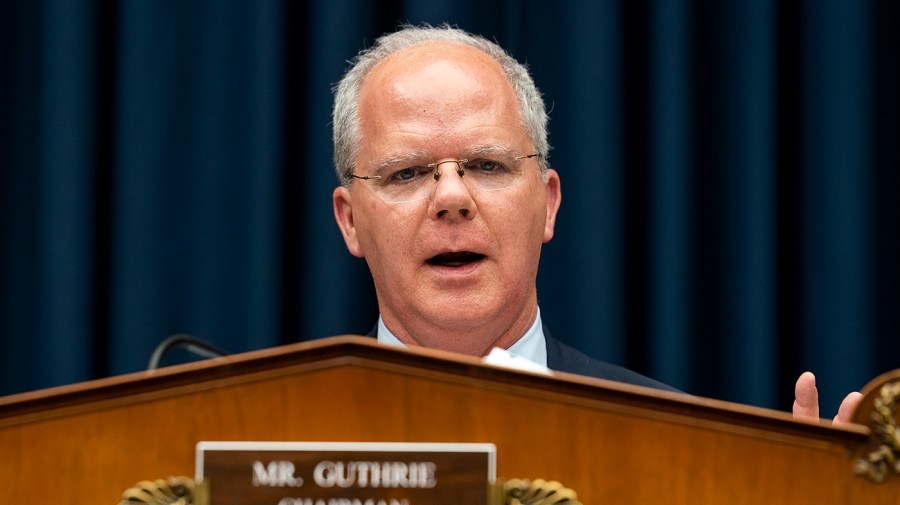

Professor Matt Hepworth, the lead investigator from the Lydia Becker Institute of Immunity and Inflammation at the University of Manchester, highlighted the profound implications of their findings. He stated, “Stroke is a devastating neurological event but also has many long-term consequences that can leave the patient at risk of airway infection, as well as gastrointestinal complications.”

Professor Hepworth emphasized the importance of understanding how the gut’s immune system is disrupted following a stroke and how this disruption may affect the management of beneficial gut bacteria. “We now think these immune changes might contribute to the intestinal symptoms and long-term complications seen in stroke patients,” he added.

As the focus remains on stroke prevention and early intervention to minimize damage, this research uncovers new dimensions of secondary pathologies affecting the body. These insights could pave the way for targeted therapies aimed at alleviating immune-driven symptoms in stroke recovery, ultimately enhancing patients’ quality of life.

The study, led by Madeleine Hurry and colleagues, highlights the need for continued investigation into the gut-brain axis and its implications for stroke recovery. The findings indicate a promising avenue for future research and potential therapeutic strategies.

More information about this study can be found in the article by Hurry et al., titled “Cerebral ischaemic stroke results in altered mucosal antibody responses and host-commensal microbiota interactions,” scheduled for publication in Brain, Behavior, and Immunity in 2026.