Archaeologists in the ancient Egyptian city of Tanis have made a groundbreaking discovery involving the funerary practices of two pharaohs. A French archaeological mission led by Frédéric Payraudeau from Sorbonne University uncovered a collection of 225 funerary statuettes linked to King Shoshenq III, but intriguingly, they were located in the tomb of King Osorkon II rather than Shoshenq’s own burial site.

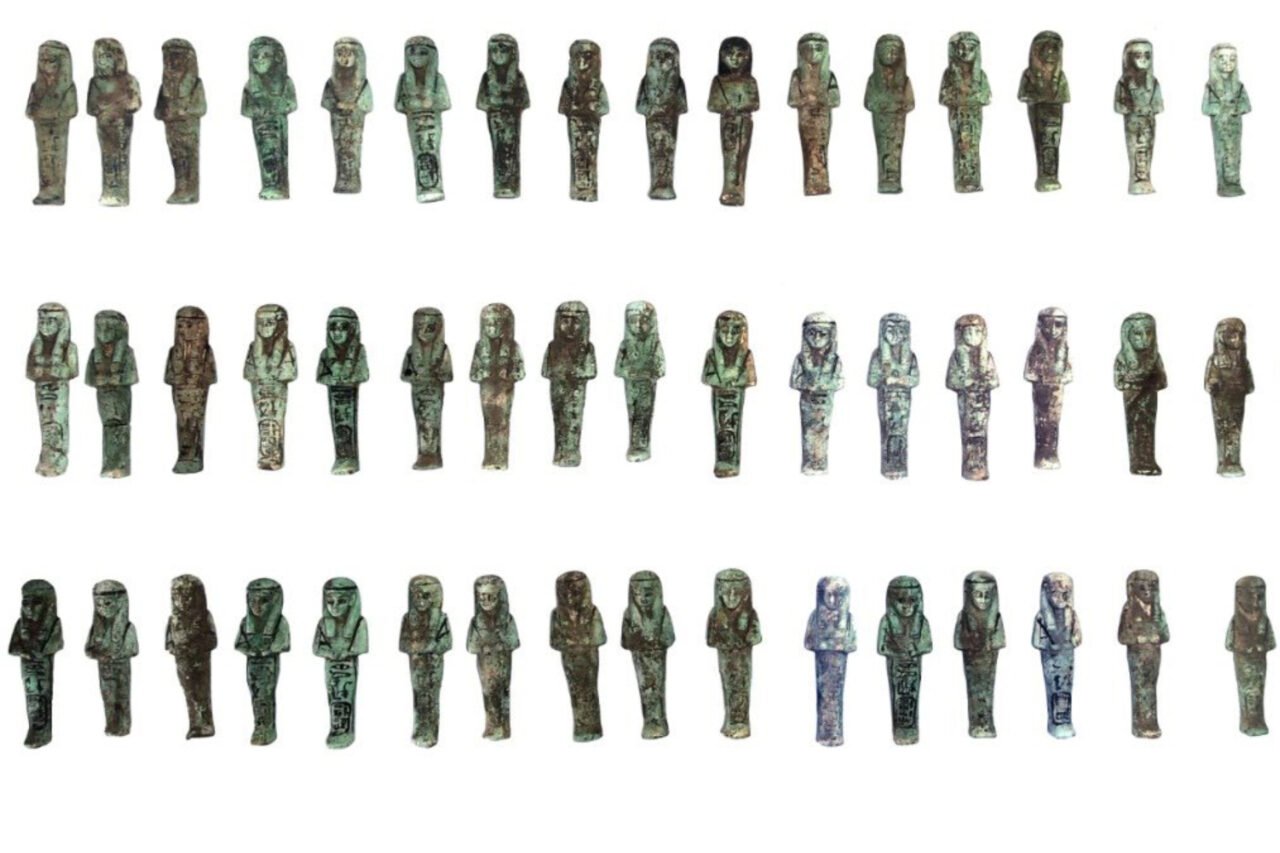

The findings suggest a complex relationship between the two pharaohs, shedding light on the practices surrounding the afterlife in ancient Egypt. The statuettes, known as ushabti, were intended to serve the deceased in the afterlife, acting as helpers at the behest of the gods. This discovery, which includes new inscriptions found on the walls of the northern chamber of Osorkon II’s tomb, was announced by Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

This revelation has sparked interest in the historical dynamics of tomb allocations in Tanis, located near the modern-day city of San el-Hagar. According to Payraudeau, the presence of Shoshenq III’s ushabti in Osorkon II’s tomb raises questions about the burial customs of the time. “The presence of the shabtis near the anonymous sarcophagus and also inscriptions on the connected wall indicates clearly that Shoshenq III was buried here and not in his own tomb,” he stated.

Shoshenq III and Osorkon II were both prominent figures of the 22nd Dynasty, which lasted from approximately 945 to 730 BCE during Egypt’s Third Intermediate Period. This era is characterized by significant political fragmentation and conflict. As noted by Payraudeau, Shoshenq III’s reign was particularly tumultuous, marked by a bloody dynastic war that pitted northern and southern factions against each other.

Osorkon II’s tomb has long been recognized for its treasures, famously known as the Tanis Treasures, discovered in 1939 and currently housed in the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir. The recent findings were made during preparations for a conservation project, indicating that even established historical artifacts can yield new insights.

While it remains uncertain whether Shoshenq III was originally interred in Osorkon II’s tomb or if his burial items were relocated for safekeeping, Hisham Hussein, head of the Central Administration of Antiquities of the Maritime Region, emphasized the significance of the discovery. “We are still investigating the implications of these findings,” he remarked.

In addition, the team plans to conduct further studies on the newly discovered inscriptions, which may offer additional context regarding the relationship between these two rulers. The complex nature of their afterlife arrangements suggests that Shoshenq III anticipated a grand existence beyond death, evidenced by his request for at least 225 helpers.

This discovery not only enriches our understanding of funerary practices in ancient Egypt but also reflects the intricate histories of its rulers. As researchers continue to analyze these findings, they aim to unravel more mysteries from a time when the afterlife was deeply intertwined with the political landscape of the pharaohs.