Recent research has uncovered a compelling link between cosmic rays from supernovae and the formation of Earth-like planets. A study led by Ryo Sawada and published in Science Advances suggests that the early solar system may have benefited from a “cosmic-ray bath,” which facilitated the creation of short-lived radioactive elements crucial for planetary development.

For decades, scientists believed that the presence of short-lived radioactive elements, such as aluminum-26, in the early solar system was a result of a nearby supernova explosion. This explosive event was thought to enrich the solar system with materials that contributed to the formation of rocky planets like Earth. However, the classic model raised questions due to its reliance on precise conditions. The supernova needed to explode at just the right distance to inject these materials without destroying the protoplanetary disk.

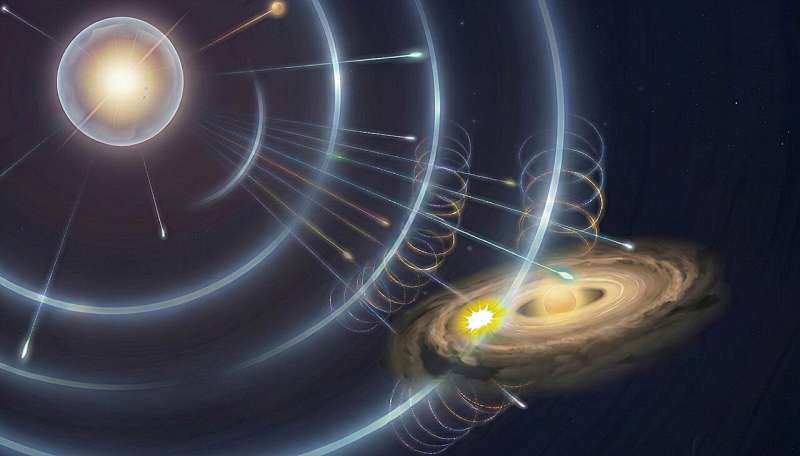

The traditional understanding posed a rare scenario, leading Sawada to seek a more comprehensive explanation. As an astrophysicist focused on supernova explosions and cosmic rays, he recognized that supernovae are not merely explosive events; they are also powerful particle accelerators. The shock waves generated by these explosions produce vast quantities of high-energy cosmic rays, which are often overlooked in models of solar system formation.

In their study, Sawada and his colleagues conducted numerical simulations to explore the interactions between cosmic rays and the protosolar disk. Their findings indicate that when cosmic rays collide with the disk, they can initiate nuclear reactions that generate essential radioactive elements, including aluminum-26. Surprisingly, this mechanism operates effectively at distances of approximately one parsec from a supernova, a range commonly found in star clusters.

The research indicates that this scenario removes the need for an extraordinary coincidence for Earth’s formation. Instead, it suggests that the young solar system merely needed to exist within the same stellar environment as a massive star that would eventually explode. This phenomenon, termed the “cosmic-ray bath,” offers a more universal perspective on planetary formation.

Sawada emphasizes the broader implications of this work. If cosmic-ray immersion is a frequent occurrence in environments with sun-like stars, then the conditions that shaped Earth could be more common than previously thought. This realization challenges the notion that Earth-like planets are rare, suggesting instead that many rocky planets may share a similar thermal history.

While the study does not imply that supernovae guarantee the existence of habitable planets, it underscores the interconnectedness of astrophysical processes. The research highlights how cosmic-ray acceleration, typically studied in high-energy astrophysics, can shed light on questions regarding planetary science and habitability.

In conclusion, Sawada‘s findings remind us that understanding our origins may lie in recognizing overlooked aspects of cosmic interactions. As researchers continue to explore these connections, the potential for discovering more about the formation of Earth-like planets remains promising.

This research contributes to the broader discourse on planetary habitability and the conditions necessary for life beyond Earth. The implications of understanding cosmic-ray baths could reshape our knowledge of how planets form and evolve in the universe.