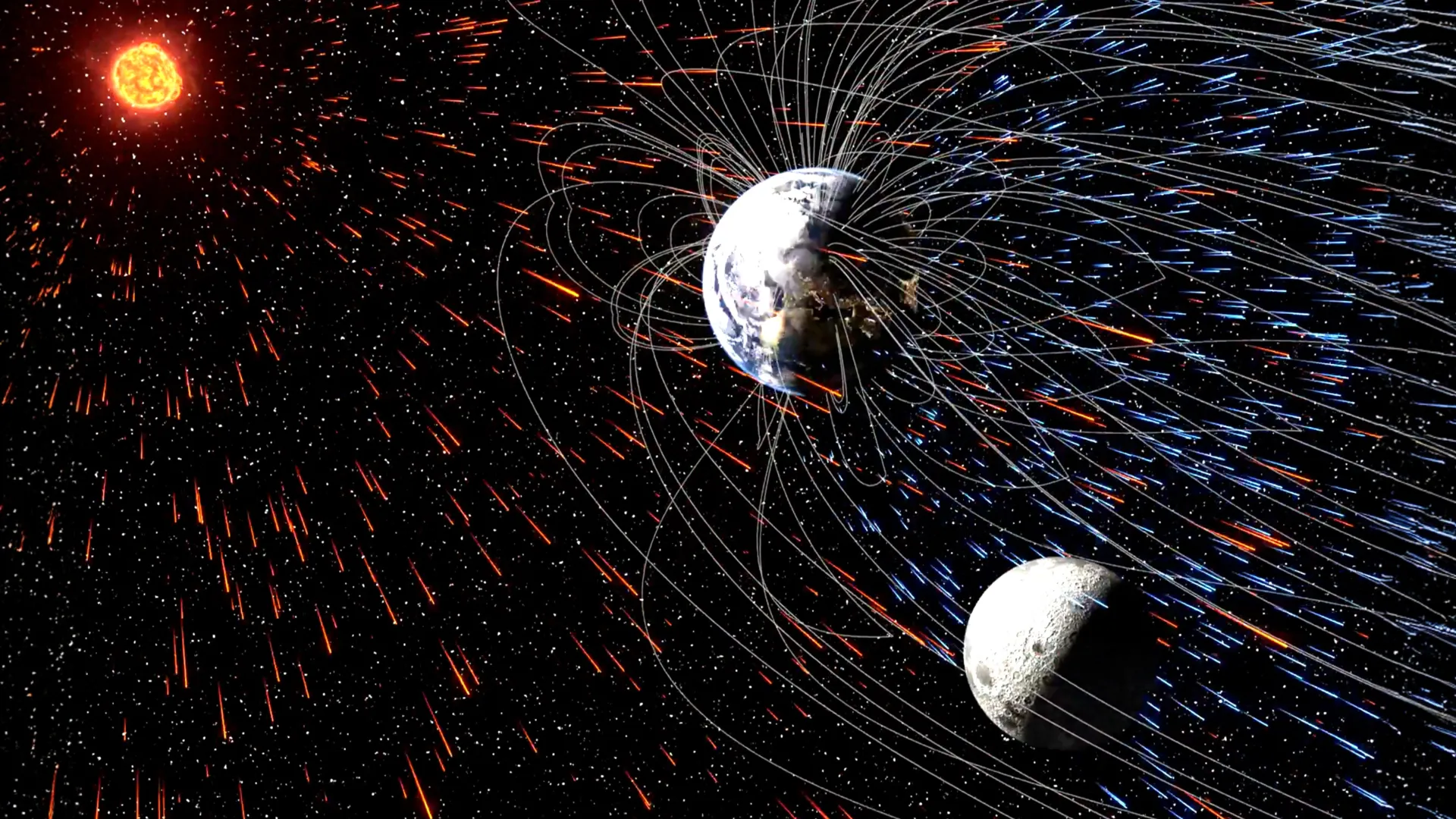

Recent research from the University of Rochester reveals that Earth has been sending tiny particles from its atmosphere to the moon for billions of years, guided by the planet’s magnetic field. This discovery, published on January 5, 2026, provides new insights into the moon’s geological history and potential resources for future lunar exploration.

The study highlights a surprising role of Earth’s magnetic field, which, rather than simply blocking particles, can funnel them along invisible lines that reach as far as the moon. This mechanism explains the presence of certain gases found in samples collected during the Apollo missions and suggests that lunar soil may serve as a long-term archive of Earth’s atmospheric history.

Research led by Professor Eric Blackman from the Department of Physics and Astronomy indicates that the transfer of atmospheric particles to the moon is facilitated by the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emitted by the sun. Blackman stated, “By combining data from particles preserved in lunar soil with computational modeling of how solar wind interacts with Earth’s atmosphere, we can trace the history of Earth’s atmosphere and its magnetic field.”

The findings challenge previous assumptions about how these particles could travel such vast distances. Earlier theories suggested that atmospheric transfer could only have occurred before Earth’s magnetic field developed. This new research indicates that the magnetic shield has actually enabled a continuous movement of material from Earth to the moon over billions of years.

Understanding the Particle Transfer Process

To delve deeper into how atmospheric particles reach the moon, Blackman and his team utilized advanced computer simulations. The research team, which included graduate student Shubhonkar Paramanick and Professor John Tarduno, modeled two scenarios: one representing early Earth with no magnetic field and a stronger solar wind, and another depicting modern Earth with a robust magnetic field and a weaker solar wind.

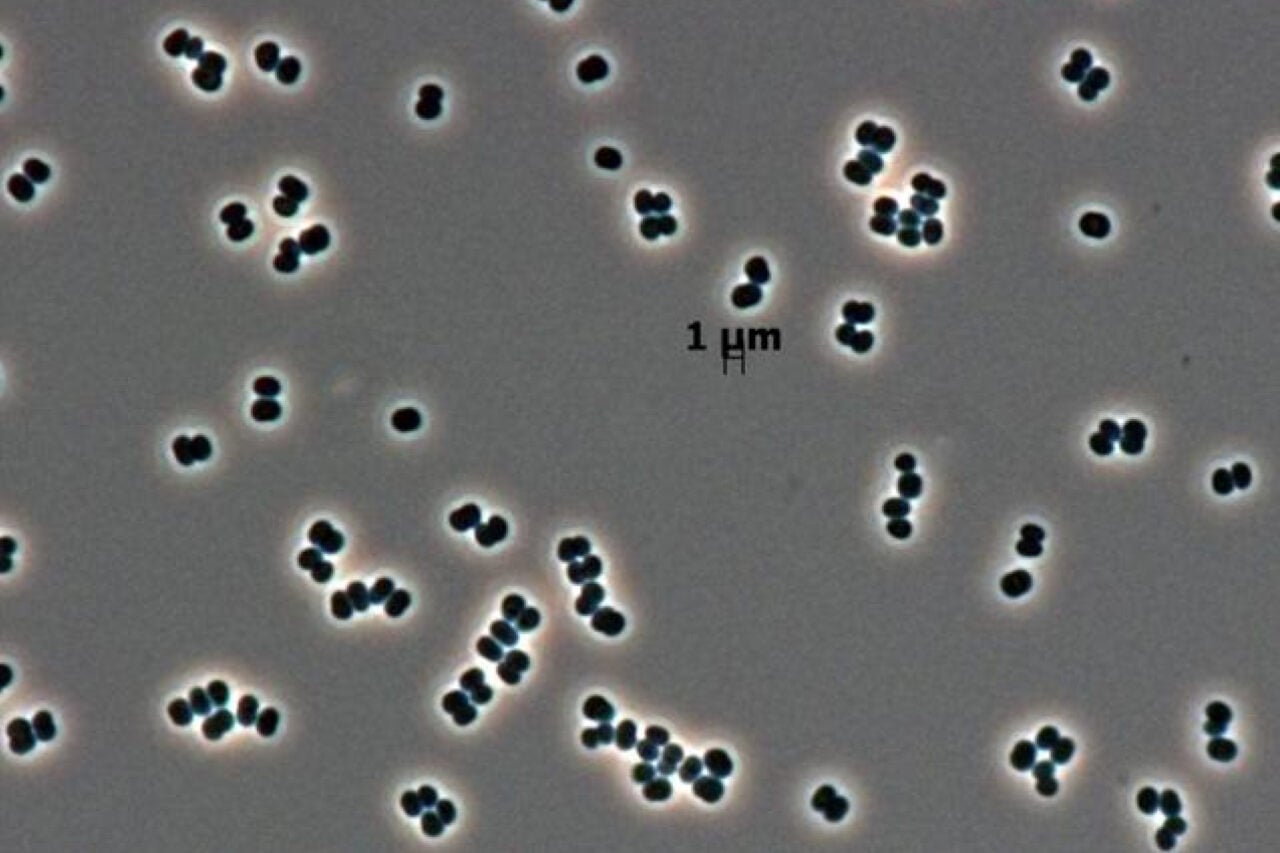

The simulations revealed that particle transfer to the moon was significantly more effective in the modern scenario. In this situation, solar wind can dislodge charged particles from Earth’s upper atmosphere, allowing them to follow the magnetic field lines extending into space, ultimately intersecting the moon’s orbit. This process acts like a slow funnel, gradually depositing small amounts of Earth’s atmosphere onto the lunar surface over eons.

Implications for Lunar Exploration

The continuous exchange of materials suggests that lunar soil may preserve a chemical record of Earth’s atmospheric evolution. This knowledge could provide scientists with valuable insights into the development of Earth’s climate and the potential for life over billions of years. Furthermore, the presence of volatile elements such as water and nitrogen in the moon’s regolith could support sustained human activities on the lunar surface, reducing reliance on supplies shipped from Earth.

Paramanick further remarked, “Our study may also have broader implications for understanding early atmospheric escape on planets like Mars, which lacks a global magnetic field today but had one similar to Earth in the past.” By examining planetary evolution and atmospheric escape across different epochs, researchers can gain insights into the factors that determine planetary habitability.

This research was partially funded by NASA and the National Science Foundation, underscoring the importance of collaborative efforts in advancing our understanding of planetary sciences. The findings not only enhance our comprehension of the moon’s history but also open avenues for future exploration and the sustainable presence of humans on the lunar surface.