Engineers at Purdue University, led by Shirley Dyke, have developed a novel approach to constructing reusable lunar landing pads using local materials, specifically the Moon’s regolith. A study published in Acta Astronautica highlights the necessity of utilizing lunar resources due to the exorbitant costs associated with transporting materials from Earth. This research aims to address the challenges faced by future lunar missions, particularly in supporting heavy rockets during landing and ascent operations.

Understanding the Moon’s regolith is critical for building durable structures. Unlike Earth, where engineers can rely on extensive material data, the properties of lunar regolith remain largely unknown. The potential for damage from rocket exhaust plumes necessitates a structured landing pad, which can mitigate risks to both the rocket and any nearby infrastructure, such as emerging lunar bases. While rockets like SpaceX’s Starship theoretically could land on any flat surface, the need for a dedicated landing area is clear.

Current Earth-based landing pads have proven effective for decades, but replicating these structures on the Moon poses unique challenges. The cost of shipping sufficient concrete to build traditional landing pads is prohibitive, making the use of in-situ materials essential. The research led by Dr. Dyke suggests that the mechanical and thermal properties of sintered regolith must be better understood to design effective lunar landing pads.

The team acknowledges that simulations using regolith analogs have limitations. According to Dr. Dyke, “simulants are called simulants for a reason.” Testing the actual lunar regolith in situ is vital for accurate data on how it behaves under the Moon’s harsh conditions. The study outlines two primary considerations for landing pad design: mechanical properties, which include stress and strain under load, and thermal properties, such as thermal expansion and contraction during the lunar day-night cycle.

As temperatures fluctuate dramatically over the lunar cycle, the expansion and contraction of the landing pad could lead to warping and cracking if not properly managed. The research indicates that for a 50-ton lander, a landing pad thickness of approximately 0.33 meters (or 14 inches) would be optimal. Dr. Dyke pointed out that making the pad thicker could, paradoxically, increase vulnerability to thermal stress fractures.

The study also identifies expected failure modes, including spalling, where chips break off due to thermal cycling. While the pad can be designed to maintain overall structural integrity, repeated rocket landings may eventually weaken it. The most significant concern remains the potential for catastrophic fractures caused by a variety of stressors, including thermal effects and improper landing angles.

To address these uncertainties, the authors propose a simple yet effective testing strategy: conducting in situ evaluations during early lunar missions. Rather than immediately constructing a landing pad, these missions could gather essential data on the regolith’s properties, facilitating more informed design decisions. This iterative approach to testing and learning could lead to safer and more effective landing pads in the future.

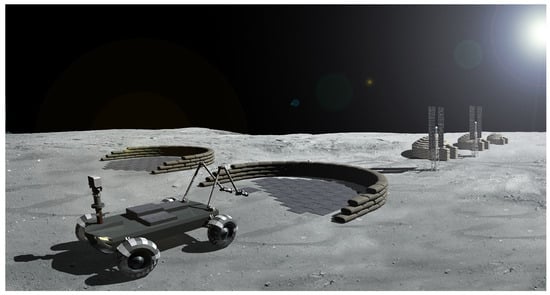

Dr. Dyke emphasizes the importance of monitoring how the landing pad deforms under load and during temperature variations. By understanding these dynamics, engineers can better predict crack formation and develop strategies to mitigate potential damage. The construction and maintenance of these landing pads will likely rely heavily on robotic systems, either teleoperated or fully autonomous, given the challenges posed by human labor in space.

As NASA and other agencies continue to advance plans for returning astronauts to the Moon, the insights gained from this research could prove indispensable. Engineers on Earth are hopeful that upcoming missions will yield valuable data to refine their models regarding the feasibility of lunar landing pads. Ultimately, this research heralds a significant step towards establishing a sustainable human presence on the Moon, paving the way for future exploration beyond our planet.