The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has made a groundbreaking discovery, detecting ultraviolet-fluorescent carbon monoxide in a protoplanetary debris disc for the first time. Research conducted by Cicero Lu at the Gemini Observatory and his co-authors, recently released in pre-print form on arXiv, reveals significant insights about the star HD 131488, located approximately 500 light years away in the Centaurus constellation.

HD 131488 is a young star, estimated to be around 15 million years old, and categorized as an “Early A-type” star, meaning it has greater mass and temperature than our Sun. This discovery builds on previous observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), which had identified a vast amount of cold carbon monoxide gas and dust located between 30 and 100 astronomical units (AU) from the star.

New infrared data from the Gemini Observatory and the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility indicated the presence of hot dust and solid-state materials in the inner regions of the disc. Optical studies further suggested the existence of hot atomic gases, such as calcium and potassium, distinct from carbon monoxide.

In February 2023, the JWST focused on HD 131488 for approximately one hour, revealing a small quantity of warm carbon monoxide gas. This gas, located between 0.5 AU and 10 AU from the star, was found to be roughly one hundred thousand times less massive than the cold gas in the outer regions of the disc. Notably, the study highlighted a significant disparity between the vibrational and rotational temperatures of the carbon monoxide molecules.

Under typical conditions, these temperatures would align due to collisions among particles, but the observations around HD 131488 showed a rotational temperature peaking at around 4,500 Kelvin, dropping to 150 Kelvin further out, while vibrational temperatures soared to approximately 8,800 Kelvin. This discrepancy indicates that the gas molecules are not in thermal equilibrium, contributing to their fluorescence.

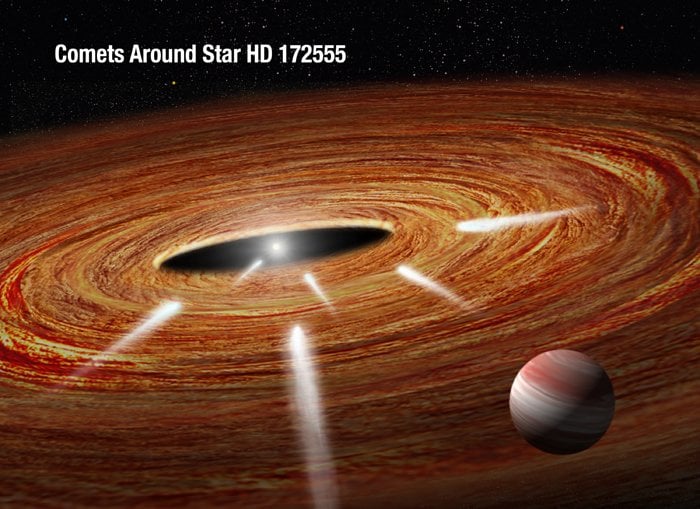

In addition to these temperature variations, the research indicated a high ratio of Carbon-12 to Carbon-13, suggesting that dust grains could be absorbing light within the sparse warm gas cloud. The study explored potential collisional partners for carbon monoxide, identifying water vapor from disintegrating comets as a likely candidate, while hydrogen appeared less probable. This “exocometary” hypothesis is a crucial finding of the research.

The origins of carbon-rich debris discs like that of HD 131488 have sparked debate among scientists. Two main hypotheses exist: one posits that these discs are remnants from the star’s formation, while the other suggests that gas is continually replenished by the destruction of comets. The evidence presented in this study strongly supports the latter theory.

Moreover, the findings have implications for planetary formation. The significant presence of carbon and oxygen in the terrestrial zone of the disc, coupled with a shortage of hydrogen, suggests any planets forming there would have elevated metallicity, distinguishing them from planets born in hydrogen-rich primordial nebulae.

These pioneering discoveries exemplify the capabilities of the JWST and underscore its potential to contribute to our understanding of star formation and planetary systems. As more observations of star systems akin to HD 131488 are made, researchers anticipate further clarifications in the debate regarding carbon-rich discs and their formation processes. This study not only sheds light on the nature of these rare systems but also paves the way for future explorations in the field of astronomy.