Recent research by Dr. Yuchen Tan and colleagues sheds new light on the settlement of Jiahu in Henan Province, China, revealing that it not only survived the abrupt climatic event known as the 8.2 ka event but also thrived socially. Published in the journal Quaternary Environments and Humans, the study challenges the prevailing narrative that such climatic shifts led to widespread destruction.

The 8.2 ka event, which occurred approximately 8,200 years ago, is characterized by significant cooling and drying across the Northern Hemisphere. Triggered by the collapse of the Laurentide ice sheet in North America, this climate change disrupted global weather patterns, including a southward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone. As a result, areas dependent on the East Asian Summer Monsoon, such as the North China Plain, faced severe drought conditions.

While many contemporary settlements around Jiahu experienced significant disruption or even abandonment during this period, Jiahu exhibited remarkable resilience. To understand how this resilience manifested, the researchers employed resilience theory alongside the Baseline Resilience Indicator for Communities (BRIC) model, traditionally used to assess modern communities’ responses to natural disasters.

Resilience Theory Applied to Ancient Societies

Dr. Tan emphasized the importance of adapting the BRIC model to ancient contexts, stating, “Our aim in adapting BRIC was to provide a transferable framework for examining how human systems reorganize in response to abrupt climatic or environmental change across a wider range of sites.” This structured approach allows researchers to evaluate how ancient societies like Jiahu reorganized and adapted in the face of environmental challenges.

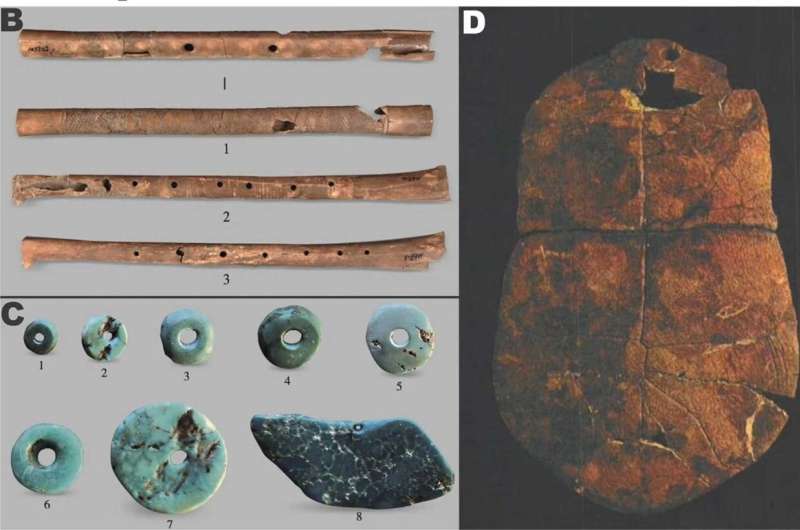

The analysis focused on three distinct phases of Jiahu’s occupation: Phase I (9.0–8.5 ka BP), Phase II (8.5–8.0 ka BP), and Phase III (8.0–7.5 ka BP). Significantly, Phase II directly coincided with the 8.2 ka event. During this phase, burials surged from 88 in Phase I to 206 in Phase II, suggesting a rise in mortality and possibly an influx of migrants from surrounding areas. Moreover, burial practices became more standardized, and the number of grave goods increased, indicating potential wealth disparities and emerging social hierarchies.

Analysis of skeletal remains from this period revealed a notable division of labor, particularly among males, who exhibited higher rates of osteoarthritis, suggesting they engaged in more physically demanding activities. This increased workforce efficiency likely enabled Jiahu to better secure food and manage the challenges posed by the 8.2 ka event.

Long-Term Implications for Jiahu

By Phase III, after the immediate effects of the 8.2 ka event had subsided, the number of burials decreased to 182, and grave goods became less common. This shift indicates that Jiahu was not only enduring but also actively reorganizing and innovating in response to the climatic pressures it faced. Dr. Tan noted that the settlement’s ultimate decline occurred after Phase III, driven by ongoing climatic fluctuations that resulted in frequent flooding. These changes rendered Jiahu’s habitat uninhabitable, leading to the collapse of its culture.

This study underscores the adaptability of ancient communities during significant climatic crises and demonstrates the applicability of the BRIC model in archaeological contexts. The findings from Jiahu provide valuable insights into how early human societies navigated environmental challenges and highlight the resilience inherent in complex social structures.

As research continues to evolve, the implications of Jiahu’s resilience during the 8.2 ka event offer a nuanced understanding of human adaptability in the face of climate change, both past and present.