The universe is expanding, yet a significant discrepancy in its expansion rate has emerged. Researchers at the University of Tokyo have introduced a new independent method for measuring the universe’s expansion, providing compelling evidence that the difference in measurements is not merely a result of error.

For many years, astronomers have depended on distance markers, particularly supernovae, to calculate the universe’s expansion rate, known as the Hubble constant. This approach places the Hubble constant at approximately 73 kilometres per second per megaparsec. In simple terms, this means that for every 3.3 million light years of distance from Earth, objects appear to recede at an accelerating rate of 73 kilometres per second.

The conflict arises when scientists utilize a different method to measure the same phenomenon. By analyzing the cosmic microwave background, which is radiation left over from the Big Bang, they calculate an expansion rate of only 67 kilometres per second per megaparsec. The disparity between these two values has been termed the Hubble tension, and its implications could potentially suggest new physics that remains unexplained.

New Technique Enhances Understanding

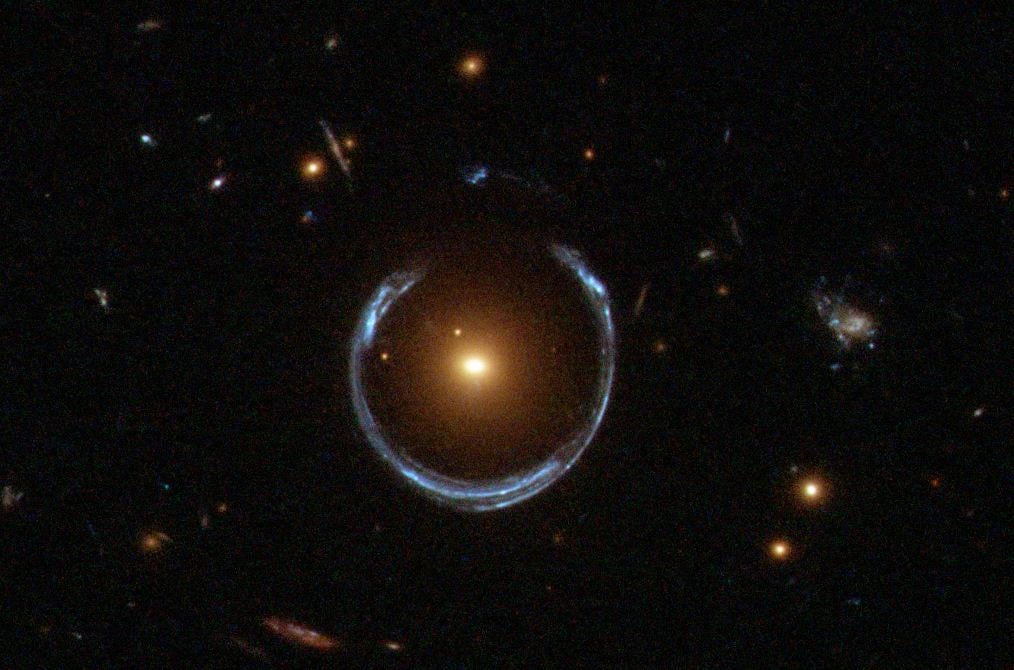

Project Assistant Professor Kenneth Wong and his research team at the Research Centre for the Early Universe have developed a technique called time delay cosmography, which offers a fresh perspective on measuring the Hubble constant. This innovative method circumvents traditional distance ladders by leveraging the phenomenon of gravitational lensing. In this process, massive galaxies bend light from objects situated behind them.

In ideal conditions, a single distant quasar appears as multiple distorted images surrounding the lensing galaxy. Each image travels along a different path to reach observers on Earth, resulting in varying travel times. By monitoring identical changes in these images occurring slightly out of sync, astronomers can determine the time difference between the paths. This approach, combined with estimates of mass distribution in the lensing galaxy, allows for calculating the universe’s expansion rate.

The research team analyzed eight gravitational lens systems, each featuring a massive galaxy that distorted light from a distant quasar. They utilized data from advanced telescopes, including the James Webb Space Telescope. Their findings yielded a Hubble constant value consistent with the 73 kilometres per second per megaparsec figure derived from nearby observations, rather than the 67 kilometres per second per megaparsec from early universe analyses.

This new approach is particularly noteworthy because it remains unaffected by potential systematic errors that might compromise traditional distance ladder methods or cosmic microwave background analyses. The alignment of the new measurement with current observations rather than early universe predictions strengthens the argument that the Hubble tension reflects a real physical phenomenon.

Future Research Directions

At present, the precision of this measurement stands at approximately 4.5 percent. To validate the Hubble tension definitively, scientists aim to improve this precision to between 1-2 percent. Achieving this requires analyzing additional gravitational lens systems and refining models of mass distribution within the lensing galaxies. The greatest challenge lies in accurately determining how mass organizes itself within these galaxies, although researchers generally assume mass profiles consistent with observational data.

This research represents decades of collaboration among various international observatories and research teams. If the Hubble tension is confirmed as a genuine phenomenon, it could herald a new understanding of cosmology, fundamentally altering our comprehension of the universe’s evolution. As the quest for knowledge continues, the implications of these findings may pave the way for groundbreaking advancements in the field of astronomy.