For the first time, researchers at Lund University have demonstrated how cells prevent damage from free radicals, small oxygen molecules that can be both beneficial and harmful. The groundbreaking study, published on December 22, 2025, in the journal Nature Communications, reveals that cells possess a mechanism to close off access to harmful substances like hydrogen peroxide.

Maintaining a delicate balance between useful and harmful oxygen molecules is crucial for cellular function. Hydrogen peroxide, commonly found in disinfectants, plays a vital role in signaling within cells when maintained at low levels. However, excessive concentrations can lead to cell damage and even death.

According to Karin Lindkvist, the study’s lead researcher and a professor at Lund University, “Our cells produce free radicals when we inhale oxygen. Previously, it was thought that hydrogen peroxide could flow freely through the cell membrane channels, but we have shown that these channels have a protective system.”

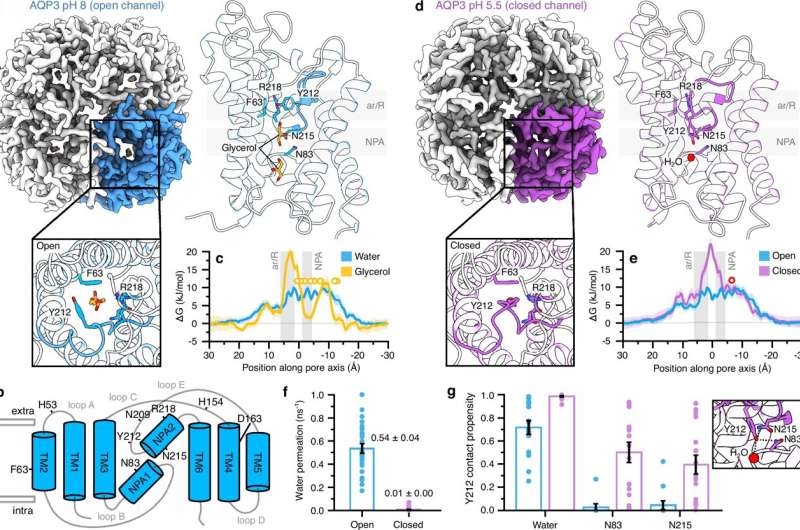

Advancements in cryo-electron microscopy allowed researchers to visualize how these cellular “doors” function. Normally, the channels are open, permitting the entry of molecules such as hydrogen peroxide, water, and glycerol. Yet, when hydrogen peroxide levels increase outside the cell, these molecules bind to the channel’s exterior, effectively locking it and preventing further entry.

“This discovery was surprising,” said Lindkvist. “It was like witnessing the cell actively closing the channel to protect itself from harm. This mechanism acts as automatic protection against dangerous levels of hydrogen peroxide entering the cell.”

The findings shed light on how cells defend against stress and regulate free radicals. This knowledge could have implications for understanding various medical conditions, including diabetes and cancer. For instance, cancer cells generate excessive free radicals during rapid growth but often survive despite this stress. Lindkvist suggests that these cells may utilize similar channels to expel excess radicals.

“Our next study will explore whether blocking these channels can lead to the death of cancer cells,” she added.

This research not only enhances our understanding of cellular defense mechanisms but also opens new avenues for therapeutic interventions. As scientists continue to unravel the complexities of cellular interactions, the potential to develop targeted treatments for diseases linked to oxidative stress becomes increasingly promising.

More information on this research is available in the article by Peng Huang et al., titled “Structural insights into AQP3 channel closure upon pH and redox changes reveal an autoregulatory molecular mechanism,” in Nature Communications (2025).