The integration of robotics and smart controls in manufacturing does not diminish the importance of tool geometry. Despite advances in technology such as automated loading systems and real-time data monitoring, the fundamental aspects of cutting tools continue to dictate operational efficiency. Manufacturers must recognize that effective tool geometry is essential for ensuring that automated processes operate smoothly and yield high-quality results.

Understanding Tool Geometry’s Role in Modern Manufacturing

While smart CNC systems and robotics have transformed the manufacturing landscape, they do not alter the basic physics of how materials are cut. Elements such as helix angles, rake angles, flute counts, edge preparation, and corner geometry are critical in determining cutting forces, heat generation, chip flow, and surface finish. If these variables are not optimized, even the most sophisticated systems may struggle to maintain productivity and quality.

According to research conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), projects that explore the intersection of automation and artificial intelligence (AI) assume that the selected cutting tools are fit for purpose. AI tools enhance processes built on sound geometry; they do not rectify issues stemming from poor choices in tool design. As manufacturers increasingly rely on AI-enhanced monitoring systems to identify problems such as chatter and overload, the underlying geometry remains the baseline that influences how often these challenges arise.

The Impact of Geometry on Process Robustness

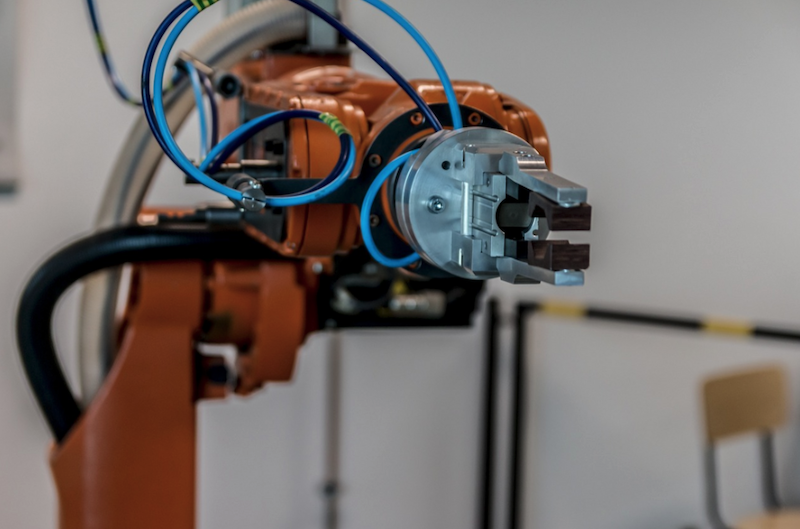

In job shops that operate with high variability in production tasks, the correct selection of tooling becomes paramount. A robotic cell may switch from machining stainless steel brackets to aluminum housings within the same day. While the CNC parameters can be adjusted programmatically, the geometry of the tools dictates how effectively these changes can be executed.

A recent study on machining quality revealed that small adjustments in tool micro-geometry, such as edge radius and rake angle, can significantly impact cutting forces and surface roughness. For instance, optimizing these parameters led to reduced cutting forces and improved surface quality, which directly enhanced consistency and tool longevity across different machining operations.

The differences in tool design are not merely academic; they have real-world implications. A polished 3-flute end mill with a high helix angle is typically more effective for aluminum than a general-purpose 4-flute option. Selecting the wrong tool can lead to issues like chip packing, which may disrupt production even with advanced monitoring systems in place.

As robots take on more roles in manufacturing, ensuring process robustness becomes vital. Unlike human operators who can adjust based on auditory cues, robots execute tasks relentlessly. Therefore, tool geometry serves as a crucial defense against failures that go unnoticed until production quality declines. For example, a small corner radius can prevent chipping when machining hard stainless steel, thus extending tool life and maintaining dimensional accuracy.

Implementing Effective Geometry Strategies

To maximize the benefits of advanced CNC and robotic technologies, manufacturers should formalize their approach to tool geometry. This can start with the development of standardized tool families categorized by material and operation rather than merely by diameter. For example, specifying high-helix, polished 3-flute tools for aluminum and low-helix, multi-flute designs for hard steels can lead to more consistent outcomes.

In addition, it is essential to integrate geometry considerations into process approvals. When introducing a new part into a robotic cell, it is not enough to simply verify feeds and speeds. Measures such as helix angle, flute count, and corner geometry must also be examined to ensure compatibility with the machining environment. Questions like whether the flute configuration allows for effective chip removal or if the corner design can handle the expected engagement should be prioritized.

Feedback loops should also be established to refine tooling standards. When specific geometries consistently yield better results, such as improved surface finishes or fewer overload alarms, these should be documented as best practices for similar future projects. Over time, this will create a comprehensive library of geometries that support the desired automated processes.

In conclusion, while smart CNC controls and industrial robots provide tools for optimization, it is ultimately the geometry of the cutting tools that defines the quality of the machining process. By placing greater emphasis on tool geometry as a primary design consideration rather than an afterthought, manufacturers can enhance the efficacy of their automated systems and achieve greater operational success.