The closure of the Pakistan-Afghanistan border has left trade paralyzed and disrupted the lives of countless individuals reliant on this crucial route. For over three months, Afghan truck driver Anwar Zadran has been stranded in Pakistan, unable to deliver a truckload of cement from Nowshera district to Kabul. The situation worsened in mid-October when both countries imposed border restrictions in response to escalating hostilities.

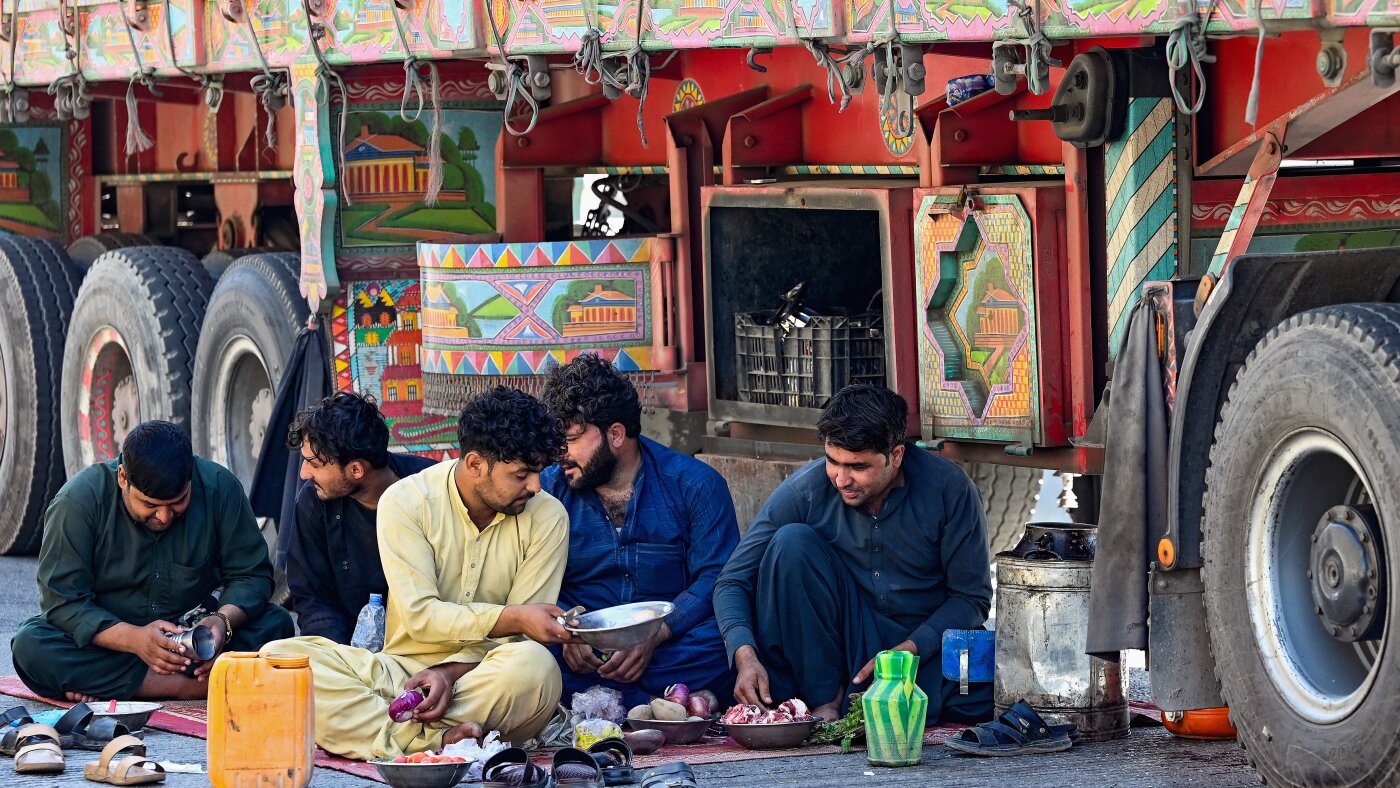

Zadran now spends his days with fellow drivers at roadside tea stalls, anxiously awaiting news of eased restrictions at the Torkham border crossing. Dressed in the same thin clothes he wore when he arrived, he endures the harsh transition from warm days to freezing nights in his truck. “The people are destroyed and the goods are damaged as well,” he expresses, wishing for the border to reopen soon to alleviate their plight.

The border, which stretches over 1,600 miles through challenging terrain, typically sees hundreds of trucks pass daily. In recent years, closures have generally resolved within days or weeks. However, this shutdown has extended beyond 100 days, marking the longest closure of its kind in decades, with no resolution in sight. The impact is felt not only by individual drivers like Zadran but also by the broader economy, as trade between Pakistan and Afghanistan has ground to a halt.

This closure is part of a larger dispute between the two nations regarding a troubling surge in militancy, particularly along the border region. Pakistan has accused Afghanistan of harboring groups responsible for attacks within its territory, a claim the Taliban government in Afghanistan denies. The Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, known as TTP, has intensified its activities since the Taliban took control of Afghanistan in 2021.

Tensions escalated in October when military exchanges occurred across the border. Despite efforts at peace talks in Istanbul, Doha, and Riyadh, no agreement has been reached. Following a ceasefire, accusations flew between the two governments, with Pakistan alleging that Afghan airstrikes resulted in civilian casualties—a claim that Afghanistan disputes.

Pakistan’s Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif indicated that the border closure was a necessary measure as the Taliban could not assure the cessation of militant activities. “We didn’t want to, but they forced us,” he remarked. Conversely, the Taliban accused Pakistan of using the closure as a tactic to impose economic pressure.

Business leaders in Peshawar, approximately 40 miles from Torkham, are urgently seeking alternative routes to sustain trade. Shahid Hussain, a trader, has outlined potential paths for his exports through China. However, he notes that existing policies regarding transit trade with China are unclear. Another route through Iran poses its own challenges due to international sanctions and limited banking connections.

Hussain has estimated losses of around $400,000 due to damaged and expired stock since the border closures began. With no work available, he has ceased paying his employees, likening his business, which has operated for over 20 years, to a tree deprived of water. “There’s no work,” he laments.

In January, business representatives from both countries initiated a joint committee to assess the situation, having held two online meetings thus far. The committee hopes to convene at Torkham, pending government approval. Both sides acknowledge the dire state of affairs and are attempting to persuade their leaders of the urgency required for a solution. Jawad Hussain Kazmi, president of the Khyber Chamber of Commerce and Industry, noted, “Our government has a one-point agenda, and that’s that security problems should be resolved.”

The border closures have also halted the entry of goods destined for Afghanistan from various Asian countries, including China, Malaysia, and Vietnam. Naqibullah Safi, secretary general of the Pakistan-Afghanistan Joint Chamber of Commerce and Industry, highlighted that shipping containers filled with essential goods remain stuck at the port in Karachi. He described the current situation as the worst for the private sector, with price hikes for staple items such as rice, medicine, and cooking oil becoming evident in Afghanistan.

According to spokesperson Abdul Salam Jawad of Afghanistan’s commerce ministry, exports to Pakistan saw a decrease of around $300 million last year compared to the previous year, highlighting the significant economic impact of the closures. Pakistan’s commerce ministry did not provide a response regarding trade figures.

As the border remains shut, Afghanistan is seeking to diversify its trade relationships with other countries, including India and Iran. The Taliban has approached India for assistance in facilitating the movement of Afghan goods through the Iranian port of Chabahar. Additionally, a complete ban on Pakistani pharmaceuticals has been instituted this month, attributed to quality concerns—a blockade that could persist even if borders reopen. Afghanistan relies on Pakistan for over 60% of its medicine, with annual exports valued at around $200 million.

“We fear that it will be wasted,”

cautions Tauqeer Ul Haq, former chairperson of the Pakistan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association, regarding temperature-sensitive medications that are unable to be redirected.

In Peshawar, shop owners are already feeling the repercussions of the lost business from Afghan customers, as many relied on purchasing medicines that are scarce in Afghanistan. Aslam Pervez, a local shop owner and general secretary for the Pakistan Chemists’ and Druggists’ Association in Peshawar, expressed concern for patients reliant on essential medications like insulin. “From both sides, it’s the people who are going to be the losers,” he concluded, underscoring the human toll of the ongoing border closures.

The situation highlights the urgent need for effective dialogue and resolution between Pakistan and Afghanistan, as the economic and humanitarian impacts continue to mount.