The United Kingdom is moving to eliminate jury trials for a range of crimes as part of reforms aimed at addressing a severe backlog in the justice system. Announced by David Lammy, the Justice Secretary, earlier this month, the proposal introduces a new tier of jury-free courts designed to expedite cases involving defendants facing sentences of up to three years. This initiative comes in response to a burgeoning backlog of nearly 80,000 criminal cases pending in the Crown Courts, a number projected to reach 100,000 by 2028.

The changes would affect serious offenses such as fraud, robbery, and drug-related crimes, which are currently heard in the Crown Courts. However, cases involving serious crimes like sexual assault, murder, and trafficking will still require jury trials. Notably, these reforms will not apply to Scotland or Northern Ireland, which operate under separate legal systems.

The UK’s justice system is under significant strain, with many victims waiting years to have their cases heard. According to government data, approximately 13,238 of these pending cases involve sexual offenses. Victims have reported waiting up to three or four years for their day in court, leading to widespread frustration and despair.

A report from the Victims’ Commissioner, published in October, illustrated the current crisis, highlighting the toll on victims. One assault victim shared his experience of psychological trauma and explained that the case was unlikely to proceed due to the backlog. “The police told me that the CPS (Crown Prosecution Service) were unlikely to prosecute,” he said, despite having substantial evidence against the perpetrator.

In Parliament, Sarah Sackman, the Minister of State for Courts and Legal Services, underscored the urgency of the reforms, stating on December 8, “justice delayed is justice denied.” This sentiment reflects growing concern over the long wait times faced by victims seeking justice.

Debate Over Jury Trials

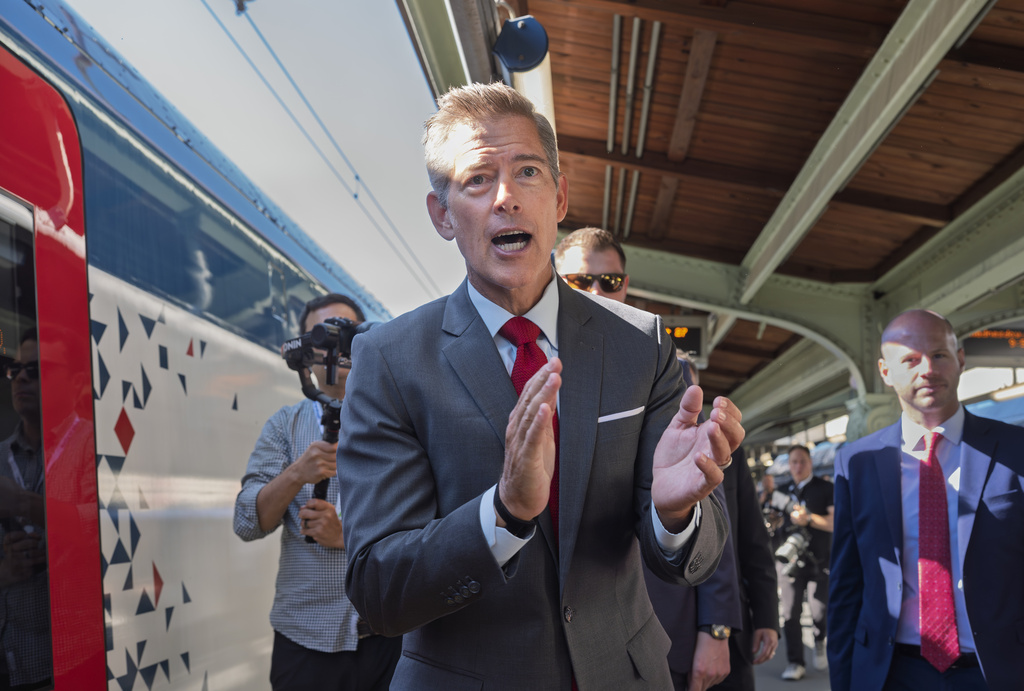

Critics of the proposed changes have expressed alarm, arguing that reducing the number of jury trials undermines a fundamental democratic right. Robert Jenrick, Shadow Justice Minister and Conservative MP, labeled the reforms a “disgrace” that erodes an “ancient right” established by the Magna Carta in the 13th century. According to a survey conducted by YouGov in November 2025, a majority of the public—54%—prefer a jury to decide their fate if accused of a crime.

Concerns extend beyond the right to a jury. Helena Kennedy KC, a member of the House of Lords, pointed out that limiting jury trials reflects a troubling belief among some politicians that the general public is incapable of fulfilling this civic duty. She emphasizes that jury service is a critical component of a functioning democracy and argues that the real issue lies in the underfunding of the justice system, which has resulted in idle courtrooms and a lack of judges.

On Wednesday, it was reported that 39 Labour Party backbenchers have urged Prime Minister Keir Starmer to reconsider the reforms. They advocate for increasing the number of court sitting days, which currently sees a restriction of 20,000 sitting days per year despite a burgeoning capacity crisis.

Advocates for the reforms argue that jury trials can prolong cases unnecessarily, particularly in a system already stretched thin. They contend that expediting processes will ultimately benefit victims, especially in serious cases.

Calls for Broader Changes

Some organizations, including Rape Crisis England & Wales, argue that the reforms should extend further. They suggest piloting juryless trials for sexual offense cases, which currently retain jurors. Their report, “Living in Limbo,” details how survivors often face retraumatization due to lengthy delays and multiple trial postponements. The charity found that many survivors are forced to withdraw from trials entirely due to the stress and time involved.

The Victims’ Commissioner report included testimonials from victims affected by the delays. One survivor of rape described how the drawn-out process ultimately compelled her to abandon the prosecution. “Too stressful, (it) took too long. It ruined my life and I thought I’d lose my family if I carried on with the case,” she stated.

Despite hopes that the reforms will alleviate some of the backlog, legal experts like Lachlan Stewart, a criminal barrister in Birmingham, caution against assuming that such changes will lead to a more efficient system. “There’s no data to show that the reforms will actually make the system more efficient,” he remarked.

As discussions continue, the UK grapples with the challenge of balancing the need for swift justice against the preservation of fundamental legal rights. The outcome of these reforms could significantly shape the future of the nation’s justice system, impacting both victims and defendants alike.